Architecture affects emotions. Every environment you are in triggers an emotional reaction. Strong or faint, the built environment has an impact on how we feel and behave. Just like art, or music, or anything else that makes people feel something. The fact that the built environment has an emotional impact on people also means that architecture can be used as a tool to influence people’s behavior. Although nothing new, it is an aspect of architecture that isn’t always explicitly considered by designers – much in the same way one might not always reflect on the relation our surroundings have with the way we think and feel. Combo Competitions wants to explore the subject further by asking participants to actively use it as a design tool.

Today’s opioid epidemic in the United States likely began during the 1980’s, when pain was characterized as something that could, and should, be treated long-term with opioids – drugs previously reserved mainly for short-term treatment due to their highly addictive nature. During the 1990’s pharmacy companies started producing opioid-based pain medication, aggressively – and falsely – promoting it to doctors as a safe and efficient way to treat pain with a very low risk for addiction. This in turn led to an increase in prescriptions by doctors, snowballing into the epidemic of today.

Opioid use disorder (OUD) can be treated through medication-assisted treatment (MAT): the use of medication combined with behavioral therapy. Along with counselling and social support, methadone is administered to patients to reduce withdrawal symptoms and opioid cravings. To ease access to methadone, medication units are being introduced as a complement to existing methadone clinics: small facilities where those enrolled in an MAT program can receive methadone, making it easier for people not living near a main clinic to collect their daily dose.

Drug use has long been regarded as a criminal problem rather than a health concern. This stigma of addiction has played a huge role in why the opioid epidemic has spiralled into a national health crisis. Consequently, it is also a fundamental part of the solution. Solving the opioid crisis requires efforts from the government by making addiction treatment available and accessible to those who need it, regardless of geographic location or socioeconomic factors – but as with many other issues, politicians won’t act until enough members of the public demand so. If enough people started viewing addiction as a health problem – and demanded it be treated as such, policy, health care and more would soon be reformed to address the demand.

The goal of Emotions, Architecture, Opioids is to design a methadone medication unit located in Venice, Los Angeles. Proposals should address the stigma surrounding opioid dependency: in addition to administering methadone, the medication unit and its setting should offer an environment that is appealing regardless if you struggle with OUD or not.

Inviting two disparate groups to share the space has the aim of dispelling prejudice and building trust, on both sides. Whether this is achieved by design, concept, the incorporation of a secondary function – or a combination of all of the above – is left to the discretion of each participant.

1st Prize

Project by: Hyjnid Metaj and Elizabeth Yeoh

Substance addiction treatment centres are often opposed due to a refusal to claim responsibility for the “other”. Recovery is not possible without empathy. This requires us to subvert the assumed ‘privacy’ of such treatment spaces in order to reveal its functions. Our project sees the methadone unit as an extension of outdoor public space — a bridge between OUD patients and the Venice-Oakwood community. Landscaping is interwoven throughout the building to reinforce treatment by inviting patients and the public in. By rethinking the accessibility and visibility of clinical space, the methadone unit becomes a stage for encounter, understanding, and healing.

The process of recovery is facilitated by three forms of treatment which are supported each by an integrated landscape: Medical Support, Social Support, and Patient Productivity. Medical Support is provided through the clinic, which addresses the physical and mental well-being of the patients. Centered within the medical support space, a reflection pool induces a tranquil meditative environment. Social Support is delivered through group activities intended to foster allyship between current patients, recovered addicts and the greater community. Social activities are screened by native plant gardens, which provide a shaded canopy for large gatherings. Patient Productivity concerns the employment and outreach opportunities available to patients at the rooftop food garden and kitchen. Long term, patients can gain valuable experience and move on to mentorship roles as they progress through their treatment.

Jury’s comments:

Here, In Our Backyard’s successful combination of well-thought-out concept, detailed building program, and appealing presentation makes it a worthy winner.

By offering treatment therapy in combination with public programs like the food garden, kitchen and outdoor dining, the proposal invites anyone to visit and organically get to know new people within the community, quietly dispelling prejudice on all sides. The secondary activities also provide visitors with opportunities for personal self-reflection rather than social activities if desired.

Architecturally the varying degrees of building permeability is compelling, and by allowing the building spatiality to follow the program functions make for a varied yet coherent design with the exterior stair as a clear invitation for people passing by to sit down for a while and for kids to play on.

The beautiful hand-drawn illustrations and story vignettes communicate the ideas very convincingly.

2nd Prize

Project by: Cindy Nachareun, Melissa Amodeo, Natalie Sandelli and Vivian Ton

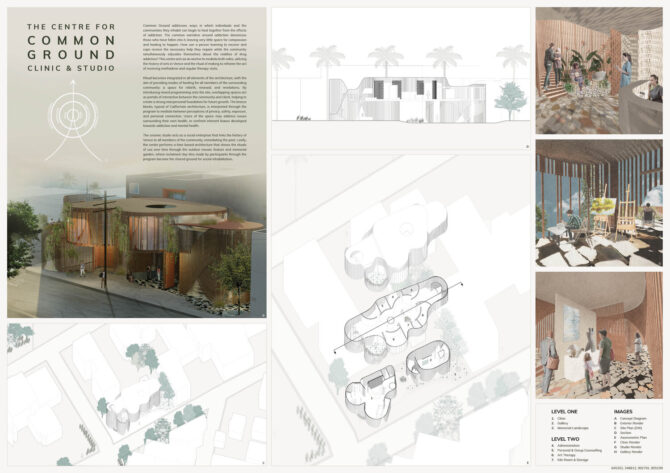

Common Ground addresses ways in which individuals and the communities they inhabit can begin to heal together from the effects of addiction. The common narrative around addiction demonizes those who have fallen into it, leaving very little space for compassion and healing to happen. How can a person learning to recover and cope receive the necessary help they require while the community simultaneously educates themselves about the realities of drug addiction? This centre acts as an anchor to mediate both sides, utilizing the history of arts in Venice and the ritual of making to reframe the act of receiving methadone and regular therapy visits.

Ritual becomes integrated in all elements of the architecture, with the aim of providing modes of healing for all members of the surrounding community: a space for rebirth, renewal, and revelations. By introducing mixed programming onto the site, overlapping spaces act as portals of interaction between the community and client, helping to create a strong interpersonal foundation for future growth. The breeze blocks, typical of Californian architecture, is interpreted through the program to mediate between perceptions of privacy, safety, exposure, and personal connection. Users of the space may address issues surrounding their own health, or confront inherent biases developed towards addiction and mental health.

The ceramic studio acts as a social enterprise that links the history of Venice to all members of the community, remediating the past. Lastly, the center performs a time-based architecture that shows the rituals of use over time through the outdoor mosaic feature and memorial garden, where reclaimed clay tiles made by participants through the program become the shared ground for social rehabilitation.

Jury’s comments:

By inviting those working to overcome addiction – and those safely sheltered from it – to draw on the notion of art and creativity to process or understand their situation, Common Ground strikes a very convincing balance between clinic and art studio where anyone in the community is invited to attend.

Along with a gallery and an area for outdoor activity, the incorporation of these secondary functions gives people the opportunity to focus on a creative outlet while at the same time meeting and getting to know new people for who they are as a person, without any preconceived labels.

A formally unique proposal, the curving wood facade is an open and intriguing face on the street. Another nice architectural touch of the concept is the idea of paving the floor with ceramic tiles created by those attending pottery sessions upstairs, giving the clinic a continuously evolving appearance.

3rd Prize

Project by: Yiran Ma

Bringing a methadone clinic into a neighbourhood can be troublesome. It is risky, it is scary, it is controversial. It can be easily misunderstood as a “gathering location for the addicts”, a “place to ask your children to avoid”, or even a “stain that ruins the entire neighbourhood”. Part of the stigma of addiction comes from the exclusivity of the medication-assisted treatment, and for the majority of society, it remains unknown. The design is focused on opening the clinic to the public. A welcoming environment will be designed for patients to feel warm, intimate, and inclusive. The huge roof and the free-standing walls make the building stand out in the neighbourhood, intending to attract visitors and stimulate their curiosity to explore the building.

Engagement

While everyone is welcomed to the clinic, on the ground floor separate entrances are set for the patients and the visitors. In the clinic, the waiting area is designed as open with a great amount of natural light brought into space, providing the patients with a comfortable environment to sit down and communicate with each other. The free-standing walls separate the space with more possibilities as different levels of privacy can be achieved for interviews and consultations. On the east side of the building, a small gallery is designed for exhibitions on the opioid epidemic and the MAT program, which is open permanently to the public.

Awareness

The big roof, in a metaphorical meaning, is a shelter that equally respects and protects everyone. The radiation of this awareness should be brought more profoundly into the city. While two types of space are separated on the ground floor, the second floor is open as a community center. The translucent semifinished plastic panels make the rooftop filled with natural light yet projected from UV radiation. Weekly lectures and events will be held to enhance the awareness of the opioid epidemic, the MAT program, and the greater context of public health.

Jury’s comments:

A proposal with a strong architectural gesture, A Roof, A Fusion, A Cure has an appealing clarity of form and attempt at communal outreach. The shape and translucency of the upper level has the potential to act as a beacon in the neighbourhood, figuratively in the daytime and literally in the evening – an icon for inclusion and community activity. It has a good balance of public and private space, encouraging integration with the community while still allowing for privacy where needed. The undulating facade toward the street creates a soft and welcoming interface with the public.

The inclusion of a ground floor exhibition area dedicated to the opioid epidemic – as well as the entire upper floor focused on lectures and events – highlights the intention of A Roof, Fusion, A Cure to involve and educate the public, presumably leading to a more involved understanding of the epidemic’s impact on society, and how to help.

The muted playfulness of color palette and illustration style helps to reinforce the inviting character of both building and presentation.

Honorable Mention

Project by: Zishi Li

As the prompt suggests, the stigma around opioid abuse is where the conflict between the patients and members of Venice’s resident community lies. The proposed design is meant to not only accommodate the immediate needs of a methadone clinic, but also suggest how a desired dynamic between patients and the neighborhood may be established with sensitive interventions from the clinic staffs. To best illustrate this situation, this project’s presentation involves two fictitious characters from those two parties—a female writer with heroine addiction and a primary school student and their encounter within the proposal’s perimeter.

Jury’s comments:

By focusing on the story of a set of plausible characters from different sides of opioid addiction, An Embodied Encounter vividly argues for the importance of empathy to combat the stigma of addiction.

At the same time pivotal aspects of concept and design are communicated through subtle hints in the text, effortlessly explaining the project without relying on traditional architectural tools of communication.

The presentation style works well with concept and story theme, with the illustrations giving the text additional depth – and vice versa.

Honorable Mention

Project by: Julian Bektashi

Architecture can play its role in improving our lives, or specific lives in this case, but it cannot do miracles. Not on its own, at least. To fight certain phenomena it takes a coordinated effort on different levels of our society. We can have no Super-hero buildings and it is important to distinguish interesting but sterile intellectual exercises from design solutions that can actually work in real life. Keeping this in mind, I started developing the project by considering 4 simple points:

First: It should subvert as much as possible the idea of clinic, rehab or any facility of that sort. In that sense, certain materials, colours and spatial configurations ought to be avoided.

Second: Once it satisfies in full the functional and technical requirements as a treatment facility – as specified in the brief- the rest of the space should be used as some sort of diversion. An environment that can offer psychological relief. It should absolutely not feel public but rather intimate and welcoming.

Third: by taking into consideration the first two points, it should combine, if possible, treatment and diversion. This means that certain activities might be carried out, with some caution, in alternative ways in order to improve the treatment experience.

Fourth: The building should not be too complicated to build and economically viable. Should be structurally linear but yet achieve some superficial and spatial complexity through the composition of simple elements. It should have a strong identity and through its form able create value for the whole neighbourhood.

The resultant design is a timber structure, with a distinct facade around a basic rectangular volume that perfectly occupies the lot and does not exceed the local height regulations (14 x 34 x 7,5m) . It has a sheltering character, apparently closed to the outside, but its barriers are totally permeable and merely acts as protection from California’s burning sun. At its core lies a Japanese inspired garden, the main diversion. Such garden, along with other supporting spaces, intends to create a pleasant multi-purpose environment: For the waiting, for eventual therapy sessions, for dedicated events or for simple relaxation and meditation, like a secular temple. The role of the entrance facade is to best advertise the richness of the interior: It should be able to stimulate curiosity to the passing citizens. They should be asking themselves: What is this place? It would be nice to have a look inside! And it won’t really matter if they are patients or not.

Jury’s comments:

By offering a beautiful green space within the structure, the Shade-Shack merges the notion of inside and outside, and entices passers-by to enter for a moment of pause and reflection.

Consistently using exposed wood as the main building material, the structure stands out in the area, at the same time invoking curiosity. The material allows for a subtle but continuous change as the wood ages over time

Captivating renderings of the interior and clear drawing communicate the design well, as does the text justifying design decisions.