Mariana Cabugiera’s step-by-step process through the Hyperloop Desert Campus Competition (including tasks to avoid), combining science with architecture, and her leadership of the multi-national team during the pandemic.

The Hyperloop Technology has been a topic widely merchandised in the last year by Elon Musk and his Team. It is a controversial method of transportation with still so much to be refined and with its necessity for today’s society still to be clearer. It is currently at the epicentre of controversy, and it was for this reason that the competition for a Lab Campus Competition caught my interest. As an architect, how can you contribute to improving this technology, minimizing the negative impact of the new infrastructure needed to study it, learn and build it?

The Hyperloop is also not just at the centre of controversy, it is also at the peak of the current transportation technology and innovation. I have worked in many transportation competition projects for Zaha Hadid Architects – 5 airports, 2 train stations – and this is not our regular transportation Hub – the Hyperloop is the High-end of Transportation, and that presented an exciting challenge to board in.

COMPETITION BACKGROUND – The Hyperloop Desert Campus Competition

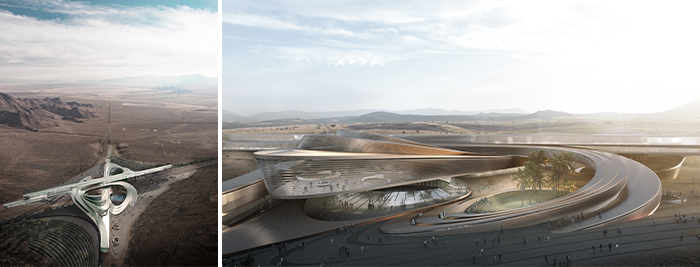

‘’In the heart of the Nevada desert, a few kilometres away from Las Vegas, the first test centre of Hyperloop – the futuristic means of transport that will connect cities and nations at a much-higher speed than planes – has been created’’ – YAC original Brief

The Hyperloop Desert Campus emerged as an answer to the increased demand of laboratory spaces that could conduct advanced studies of the Hyperloop Technology. It results from the need of a high-end study centre that is isolated from the urban scenario and able to grow in the desert limitless space. The Campus was projected to gather the brightest minds in the planet: designers, engineers, visionaries, together with ambitious students. Such a community of scientists would temporarily live and collaborate in this campus for one simple purpose: the evolution of the Hyperloop Transportation Network.

‘’The architects will be asked to shape the most recent dreams of innovation and speed through an iconic building located in one of the most majestic and suggestive contexts on the planet, The Nevada Desert‘’ – YAC original Brief

The Competition set by YAC for the Hyperloop Campus required a Landmark Building that would stand-out from its context and simultaneously blend with the surrounding landscape of the Nevada Desert. The Campus could not be a ‘’mere building’’, it had to represent science and progress simultaneously celebrating the culture of the place.

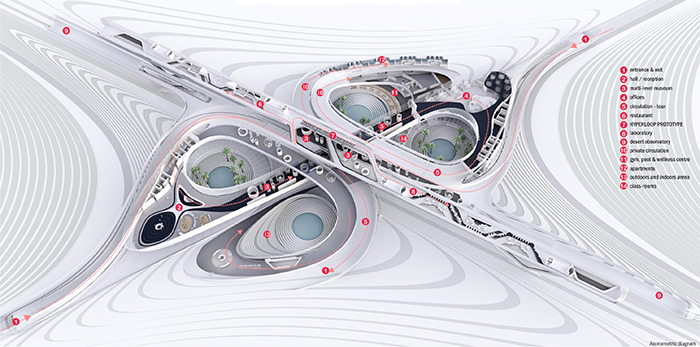

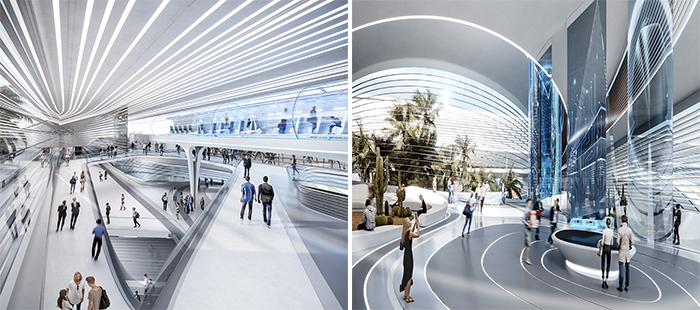

Programmatically the Campus was split by three Units with different degrees of privacy. Unit 1: Main Hall, Public Museum, Public Arena, Restaurant and Public Tour. Unit two: Classrooms and Laboratories. Unit 3: Offices, 50sqm apartments and a Wealth Centre with a spa. Square meter wise, Unit one was clearly the most dominant in the Campus, followed up by the Laboratories in which a real-scale prototype of the Hyperloop would be developed.

The Competition was officially announced in March 2020 and the deadline was set for September 2020. Of the Panel of Judges was part Ben Van Berkel (Unstudio), Winy Maas (MVRDV), Paolo Cresci (ARUP), Kazuyo Sejima (SANAA), Fedele Canosa (MECANOO), Lina Choi (Oualalou + Choi), Chad Oppenheim (Oppenheim Arch), Italo Rota (Studio Italo Rota), Hasan Calislar (Erginouglu & Calislar Architects) and Nicola Scaranaro (Foster + Partners).

FORMING OF THE TEAM

The competition was announced in early March 2020 but it caught our attention later around June. As the first pandemic lockdown had settled, I was working remotely in London for Zaha Hadid Architects, my friend Begum Aydinouglu was starting her own small practice in Istanbul and another friend of ours, Juan Carlos Naranjo was running his new own practice as well in Bogota, Columbia.

We had been colleagues and became friends while working together in a post-graduation course in London called Design Research Laboratory, three years before the competition, and went our own ways after the course had ended. I was the only one of us who stayed in London and joined ZHA, nevertheless we remained close friends and, most importantly, we had a very similar approach to Architecture, design and technology.

When starting a competition, with friends or colleagues, it is important to have a smart strategy behind the group members. I, Juan and Begum have worked together and we know how talented each of us are, but we are also aware that each of us is really good at completely different and complementary tasks. The criteria to start a strong and well-balanced team is one of the key-points when you are participating in a competition. Avoid pulling over your fun, yet lazy, friend.

The competition challenge was proposed to us by Juan, who had his own architecture practice on hold due to the pandemic, in June 2020. Begum was in the same working situation in Turkey and for me, from the moment I settled a routine while working remotely, it had become quite clear that this presented a great time to work beyond office projects, on personal projects, teaching, having hobbies and to get involved in other activities. So we accepted this challenge of working digitally together and developed a project together for this very compelling brief.

We joined the competition quite late, two months and a half before the submission. I am personally used to quick competitions – it has been my job at Zaha Hadid Architects for the last 4 years to create buildings for quick-pace projects – so there was a big excitement to design something new for the Hyperloop Competition in 2 months.

OUR PROCESS

When you start a competition the first step is typically to read and understand the brief, a task that must first be done individually. This phase is followed by what we call the kick-off meeting in which each of us presents their own approach to this brief – challenges and strategies.

There were a series of programmatic requests which became quite significant when designing the campus: the tour would have to circulate through all public spaces and have at least a visual connection with all the remaining spaces, the restaurant would have to have a visual connection to the labs and the hyperloop prototype as well. For me these requirements were suggesting a fluid visual and physical transition between spaces and, suggesting a looping circulation inside this campus.

Beside the programmatic component of a brief there are also other spatial expectations. The Hyperloop Desert Campus was expected to seamlessly combine the technological look and feel of the Hyperloop Speed Train and the earthy/rocky look and feel that is part of Nevada’s Desert identity.

It is quite common and very interesting for an architectural brief to ask for a landmark and yet to expect you to blend with the context. It is an expectation that I am confronted with in most of ZHA client’s briefs. What it reads like a contraction becomes the most interesting challenge when designing something new in architecture – to be iconic, to stand-out, and yet blend a new-built with the current city culture.

The first kick-off meeting is as important as the next ones. It seems to be a relaxed, light meeting but you should put a big amount of work into it. It is the first time you start organising ideas, expressing your thoughts and understanding your teammates’ approach as well.

As a designer in architecture my first approach to a competition is to gather all images that come to mind while I am reading the brief. Images of intentions or just quick, very abstract sketches. I appreciate the very initial visual instincts you have while reading a brief, so storing them in the beginning is usually very important. For the kick-off team meeting I compiled a ‘’mood board’‘ with these images and sketches that reflect spatial and programmatic intentions. They can vary from very conceptual ideas to case studies of built projects with the same programme or the same spatial qualities. This is not an artistic ‘’mood-board’’, it does not serve as an inspiration to design, but represents clear strategies to address the program, design, typologies and uniqueness of this brief.

From the kick-of meeting we agreed to approach the brief with 2 different strategies. This is the first lesson that I have learnt from working for all these years in competition for ZHA: spend enough time developing at least two different approaches to the brief. These 2 strategies don’t have to be opposites, they should be developed simultaneously, and should compete in quality, so in the end you decide as a team which one is better and which arguments are stronger to move forward.

After the kick-off meeting the first phase of the competition started. In this phase everyone was expected to draft a spatial intention for the project but it is mainly the designer of the team’s job to create new spaces and typologies, to model them and to present them to the team. The first phase is fully on the designer’s shoulder, but as the project moves forward this work-load gets equally distributed. It is quite important to remember that in competitions out of office there are no hierarchies, you should respect all of your team member’s opinions equally, the design of the building should be consensual.

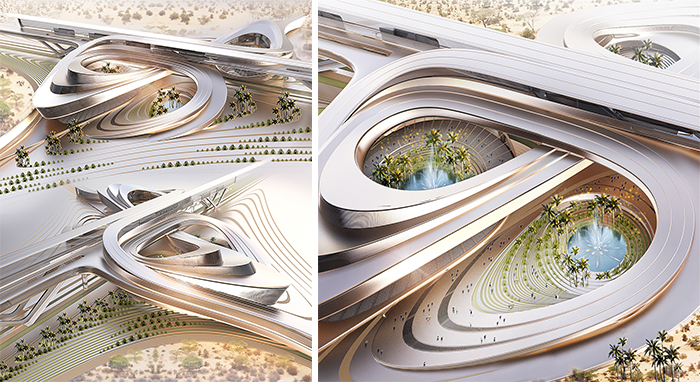

When you look at my initial sketches in red the main principles take different shapes but remain present across all studies: the idea of building in the desert that is sustainable and independent recalls an Oasis in the desert. Oasis are typically a circular patch of water with lush greenery around, they co-live in a micro environment. I decided to take the Oasis concept on board for the design creation. This circular configuration led us to research into circular campuses, like the Google Campus, which is levitating over a massive pool of vegetation. According to the Hyperloop Campus’s Brief the programmatic division and public spheres were split in 3 units, therefore this led me to create three different oasis. In the end, the requirement of spatial fluidity – physical and visual – combined with this public tour that should run across all units, created the idea of a building that is looping around three very unique green courtyards, levitating over-ground or softly framing them. Since the beginning this became the main design strategy behind our project.

Moving forward, these concepts took very different shapes in very different design schemes. All these 3D studies and the final project were fully modelled in Autodesk Maya – the software we use at ZHA to design – and simultaneously exported to Rhino for sqm check, scale and solar analysis. From Rhino we also exported simple boxes that represented each unit sqm to serve as rough guidelines when designing the spaces in Maya. This design phase, exploring completely different options, should take around 2 weeks. As one option becomes clearer, the design work should be focused on producing different options with a similar approach.

The team was meeting every week, over zoom, juggling Colombia time zone, London time zone and Turkish time zone. With daily messages of ideas and thoughts, this fully digital team-work proved to work quite well. For the first 4 weeks we battled with 2 different sketches that I had developed, and although I was clearly convinced by a specific one, the rest of the team wasn’t. This is again an important part of any competition – it is very common to disagree and it should be normalised in the team without being taken personally. When the team disagrees with your work, you either put in extra work-effort to convince your partners and improve the design option you like better, or you are intrigued enough to develop a sketch that is not your preferred one but it has valid and strong points made by them. It is something that I am confronted with every day at work and I usually do both: I work to convince the team but also like to test other ideas. Therefore, I put in double work on these two concepts.

The first option was the first design sketch to be recognised by the team as worth moving forward with. Despite it being my preferred option, in the end it was discarded and replaced by mutual agreement. This option had in its core the looping concept around 3 very distinguished courtyards – the green oasis. It proposed an experience of the building from top to bottom – as you would start from an escalator on the ground reaching the top floor first and looping your way down to the building. The three courtyards gathered the 3 programmatic units.

As a team we have identified the following pros and cons:

- Pros: It was smaller in scale, irreverent in form, solid and concise. The loop was single and non-ambiguous which made the character of each courtyard stronger and unique

- Cons: It was too alienated from its surroundings, the small scale didn’t reflect a Campus scale, it was short in square meters – as per brief.

For these reasons we split the programmatic units in 4, I started designing a 4 courtyard building with 2 symmetric and convergent loops, travelling around the spaces and culminating on the top floors of the building in straight lines – where the restaurant and observatory are. In this option, unlike the other option, the building was not described only by a single loop. The design included more flat areas and straight elements that where strongly part of its shape as means to connect to the future network for the Hyperloop that will run above ground.

Option one was discarded but it still remains my special one. I will hopefully recycle it for a future project.

In the end, I caught myself putting some extra time designing this second idea, so it was clear, I was more excited about it. The Hyperloop expanded from three courtyards to four, which made it grow in scale to a campus-like typology. We adopted the idea of a highway clover as the concept for looping buildings with a fluid circulation. The idea of having this loop levitating around the green oasis was kept, but instead of three programmatic units, we created a fourth loop for a special unit: the public open-air arena.

The shape, typology and design of our Hyperloop Campus was now agreed and ready to move forward to plans, section, interiors and detailed design.

From the moment after the design is ‘’signed-off’’ by the team it is the designer’s responsibility to decompose the building by its architectural components – roof, floor, walls, exterior envelope, interior envelope, landscape – to export it (in our case from Maya to Rhino) and share it with the rest of the team members so the team-work can begin.

Once the second phase starts, we begin daily coordination – emails, messages, zoom meetings – with the planning members (2d) and the designers (3d). This is the trickiest part of the process, since all of us have to be coordinated. Plans need to be coordinated with 3d and 3d members need to work with the plans. The design should continue to be refined and to move forward to interiors, structure, cores, ‘’meps’’, façade systems. For this to happen the person doing plans and dealing with accurate measures and areas has to feed the designer with these spaces roughly refined and expect to receive them designed later on by the designer.

The meetings for the competition were kept weekly but were taking a lot more time, 3 to 4 hours, since every member was working quite a lot and producing very relevant work. We had incredible help from some of the office employees of Juan’s Office – Left Angle Partnership – especially when it came to 2d drawings. All work produced weekly was subject to opinions during the team meeting, and even though we were a team of just 3 people – the process started to be quite intense. It is traditionally the longest phase – there is a lot of back and forth.

Again, it is quite important to remind yourselves that all opinions are valid and that there is no hierarchy. You should respectfully review everyone’s opinions and even ask for them, so all members are engaging with this project, which will also work in your favour later on.

As the exterior envelope of the building gets refined, from the design point of view, it becomes quite important to select the most important interior spaces for further detail. This is a crucial part of any competition. The realisation that the project is not going to be built tomorrow or in the next year makes it very clear that you should NEVER detail all spaces of your project. As controversial as it may seem, and some of us really have the impulse to solve a building in its totality, it is a big mistake to spend time designing and modelling spaces that will never be seen. Your jury will only see the spaces that you show on your renders and visuals, all the other remaining spaces will forever stay in the dark. Therefore I really urge you to take your time selecting the most important spaces that solve the brief and explain your building and from that point on focus your work and time only designing these.

For the Hyperloop the spaces that were crucial from a programmatic point of view were: The Main Hall – as it is your starting point to your journey in the project; The Hyperloop Prototype Lab, with the visual connection to the Restaurant and the Museum. From a spatial point of view the spaces that explain the concept of the building better were: of course the Oasis Courtyards, the integration with the context from a human perspective, the integration with the context from an abstract perspective and the looping perception of the spaces and circulation. The design effort was allocated to these spaces only.

In the plan all spaces need to show capacity to arrange the functionality basics – from the back of house spaces, to bathrooms, to furniture arrangements. Yet, there is no need to have this in 3d, as that makes your file unnecessarily difficult to work with. From a workflow point of view I started creating different Maya files for each main interior space, as it is less demanding for your computer and it helps you organise your work. Each Team meeting had a theme as well so each space progressed simultaneously – for example while I was modelling the offices and connection to labs, the planners were arranging this space in 2D with accuracy with a constant feed-back loop between our files. This is the exact same process for a competition in an office.

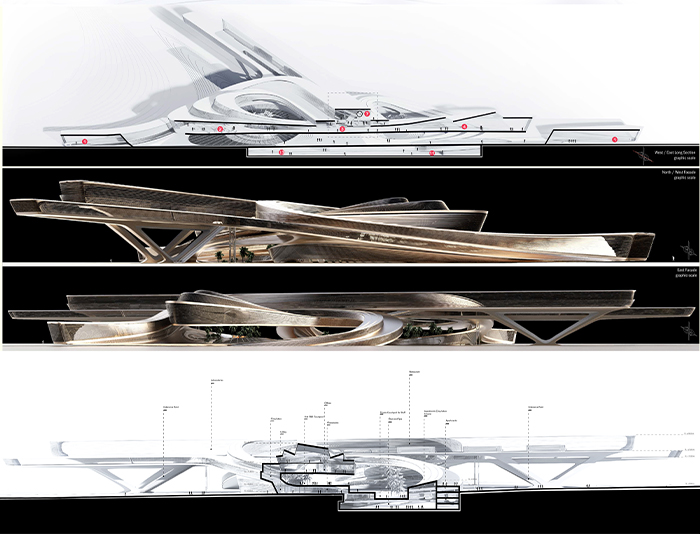

Not all design features have to be represented in your 2d drawings for a competition as well. Not all features that are modelled in 3d have to be in your 2d, since, and again, these drawings are not for construction, only the major design features should be included in. The 2D competition drawings are in a way diagrammatic and usually are requested in small scale – 1:500 and one plan probably in 1:200. This scale omits many details that you have designed in 3d. In a competition project, to reduce the time wasted in this back and forth process, the team should identify the main design features to be drawn in 2d.

This takes me to the last part of phase 2. It is the part when designers and planners ‘’divorce’’ and can work with more autonomy. In this phase the plans don’t need to match to perfection with the 3d, and while this can be viewed as controversial, remember we are not producing construction drawings so everything should simply express the project’s intention. When phase 2 is closer to the end plans need to run faster and design as well. Constant back and forth slows down the project and tires the design. Only if there is a relevant change of geometry the plans should stop their progress and include what the design is doing and vice-versa.

Phase 2 ends with frozen overall design and frozen spatial planning.

Phase 3 starts. In the Hyperloop Project we scheduled all 3 phases in a quite detailed way in Excel, so we could keep the rhythm and be on time. It is fundamental to start your project with a detailed schedule and in your schedule include at least a week as margin for delays.

We started the project with only 2 months and a half to submit, while I was working full time for ZHA which allowed me to only work for the Hyperloop Competition on weekends and after office hours, so we were on a tight schedule. For Phase 3 we planned 4 weeks and we had only 2 left in the end. Personally I consider this phase to be slightly more crucial than the other ones, it is the Post-Production Phase. This phase can be the make or break phase of your project, it is how you communicate your Project that truly shows your work to the Jury.

There are 3 different elements to consider for this phase: the 2d drawing package – with plans developed for the right printing scale, sections and small details; visuals and renders of your 3d; and Diagrams – in 2d and 3d. Typically the diagrams are left to be done last, so we split the 2d and 3d work amongst ourselves and joined forces for the diagrams in the last week.

Design wise there is still a lot to be designed but this time you should restrict yourself to the cameras that you are going to render from. That is why my “step one’’ for the post production phase is typically to select the main cameras for each space and pick – with my colleagues as well – the most important shot of the whole project, what I call ‘’the money shot’’. This render is the cover image, so it should show your project in the best way. Regardless if it is abstract or very realistic, it has to resume the qualities and intentions of your project in one image. Apart from the ‘’the money shot’’ – which was set obviously in one of the Oasis Courtyards – we decided on 4 exterior cameras and 2 interior ones. It was also decided from the beginning to outsource our renders.

Outsourcing renders is always a big question mark when you are doing a competition. Although we have enough competencies to render the project with decent quality in house, the reality is, unless you are an archi-visualizer, your ‘’homemade’’ renders will never be as good as professional ones and it also becomes a time-saver for your working schedule. It is an optional investment to pay for renders. Regardless if you win or not, in these current days your project will have a wider public exposure than before. As outsourcing renders become more and more common, their prices are also increasingly cheaper. LinkedIn is a good platform to find them. We worked with Metrica Visuals from Bogota’ quite successfully.

After all spaces were designed in detail for each camera – and this work includes all the small elements that make a big difference on a good render (pavement, light lines, furniture, balustrades, greenery, doors, etc) the 3d models were exported to Metrica Visuals. We sent separate Maya files, which I also recommend if you are outsourcing renders and have heavy interiors – one space per file and a main file for exterior views with landscape.

For this project I got carried away with the hyperloop lab little prototype and made the typical mistake of spending too much time detailing and designing something that will never be seen. It was nevertheless quite exciting to design and speculate the seating arrangement and futurist design of the Hyperloop capsules. You can see it very blurred on the background of one of the interior renders. It was an obvious example of time spent with passionate design work and total alienation of time. You can’t always be efficient and sometimes it gives you pleasure to get carried away by details never to be seen, nevertheless, when doing a competition, try to avoid them as much as you can.

In these 2 post-production weeks there is intense communication work to be done with your rendering company. Besides sending them a mood board for each space prior to their first render test, you should expect previews of each render every 2 days to do as many corrections as you can to these images. These companies are professional but they cannot guess what your building principles are, the brief intentions or your personal aesthetics. So in competitions – done in the office or out of office – the communication with the rendering company is expected to be regular and with a lot of patience from both parties.

The money shot render of the Oasis Courtyard was the image that required more attention and back and forth work, since it was the main image, there was no holding back on corrections. It ended up being my favourite image of the whole project. It really represents the satisfaction that I had when creating this Project.

Meanwhile there are a lot of diagrams that require rendering. We did most of the in-house rendering work in Keyshot which is a very intuitive software for rendering and gives you a very professional conceptual look. The Arctic view in Rhino also goes a long way when it comes to producing Diagrams. If you change the Arctic settings to also render materials the image gets even better with no need to do a lot of colouring in Photoshop or illustrate. From the Artic view I also recommend you to avoid taking screenshots and to use the tool ViewCapturetoFile – set the scale for 2 or 3 and your image will have the quality of a good-size render.

In current days I consider it fundamental that you present a chapter for sustainability when creating a new building. You can include any site analysis – solar, wind, proximity with the environment, glass reflection and heat – and present the strategies that you took on board to soften the impact of your building on the environment. For the Hyperloop Campus we focused on the principle of ‘’resiliency’’ which describes an autonomous building, able to adapt to its environment – a quality that is fundamental when building in a desert that reaches high temperatures during the day and very low at night. In this chapter we also included diagrams that explain our façade system of louvers with a specific inclination when facing a specific solar orientation. Solar panels were also integrated in our massive landscape design and a system for water collection that loops from one courtyard to the next one was also part of the green-building strategy.

It is very important to keep the efficiency while producing the final content and to confirm that you produce all the mandatory deliverables first. We started planning our from the beginning of the post-production phase, leaving a place-holder for the mandatory deliverables and organising all the renders, so we were aware that the space remained for additional diagrams. This final panel should be compiled by one person only with an overall vision for arrangement and aesthetics, I recommend you to look for Competitions panels on Pinterest for guidance. The panel was done in InDesign which I highly recommend for compiling wide size panels with heavy images.

As the final images were finished they were being added to their respective place-holder in the panel, with no unexpected problems with size and scale.

In parallel, the planning team was compiling a heavy booklet of 2d deliverables, with plans ranging from 1:1000, to 1:500 and 1:200, and 1:500 sections.

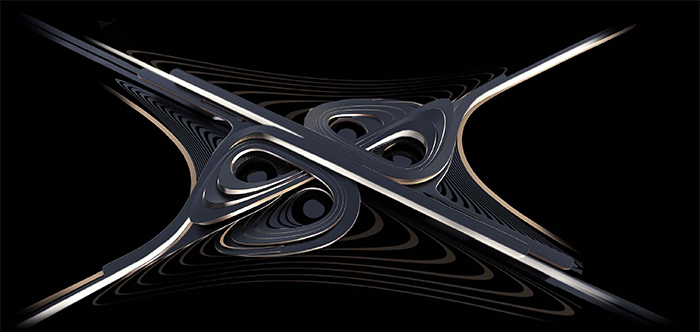

Finally, there is one very important element of the project that is often forgotten but I consider to be fundamental in any great project: the logo. If your brief states a landmark and you want your building to be a memorable Icon, it is the cherry on the cake to have one simple, abstract image that represents and resumes your project in a couple of lines, making your building distinguishable, memorable and clear. At ZHA we spend enough time developing and refining these icons. You can tell when looking at them what the main principles to create this project were.

The clearer your concept is, the cleaner should be your Icon. For the Hyperloop the concept was quite clear: four loops on a cross, representing the Oasis and the Hyperloop Mega Speed Network. This is the principle that made the Logo, and we made sure to have it repeated enough at the top or bottom of all pages.

The last 2 to 3 days of any competition are inevitably quite hectic. The Hyperloop one was no exception. We were working full time over the weekends to make it to the deadline. Because we were in very different time zones the work never stopped, and we picked on each other’s tasks every day, which created a very exciting pace for this competition.

The submission was completed at 7am Bogota time. We were exhausted but very excited for the journey we had.

In the end we were made finalists. The winners had very different principles which made us believe that the judge had a different criteria that we had while creating it – all projects were highly conceptual and less realistic. This is ok. There are many unexpected criteria for a client or a jury to prefer a project over others. It shouldn’t downgrade the quality of your project. I usually say that the ‘’Un-built’’ library of Zaha Hadid Architects is a Design Sanctuary, it has the best buildings that the world will never see. They never made it to day-light but nothing goes to waste and some of these lost projects inspire the next ones.

FUTURE CHALLENGES

This is currently the best time for you to engage in Architecture and Design Competitions. We were never so digitally connected and working remotely has proven to work quite efficiently within teams. I urge any student to gather a team of hard working and passionate colleagues and to look for a healthy competition to participate in. It is also very beneficial for an office, even if you are just starting, to spend some time developing projects that are not only commissions. It encourages the office to brainstorm ideas, push the boundaries of design and address bigger, usually international, challenges. It also places the office in International Design platforms. There are ever new websites announcing and publishing competition projects, for built and unbuilt projects. It has never been this easy, so I encourage you to give them a try.

BIO

Mariana Cabugueira is an architect and urban designer from Portugal, recently working as a Senior Architectural Designer at Zaha Hadid Architects, teaching at the Architectural Association in London and doing live workshops and webinars with students from all around the World.

Graduated from the School of Architecture in Lisbon and the Politecnico di Milano, she moved to London to explore design and technology through the postgraduate course: Design Research Laboratory (DRL) at the Architectural Association School (AA). Her research interests gravitate around parametric design, generative design, digital design and the evolution of architecture through the use of technological means, such as robotic fabrication. Her final project proposes a cluster of towers, radically different but biologically similar, in the centre of London.

Mariana joined Zaha Hadid Architects after graduating from the AA School in 2017. She is part of the Competition Cluster ever since, responsible for the high-end design projects of the office.

She was part of the design team of winning projects such us: Navi Mumbai Airport, Western Sydney Airport, Exhibition Centre Beijing, and most recently the Tower C in Shenzhen

If you would like to ready more case studies like the one above please check our annual publication

Architecture Competitions Yearbook.