Starting with a pencil and a blank page

An interview with Robert Konieczny on the importance of designing from scratch, avoiding Pinterest and listening to your failing.

Let’s start at the beginning. Where did you first get the idea to become an architect?

Robert Konieczny: It was actually my dad’s idea, which my mom later joined, and it was my parents who were trying to convince me, at the time, to try architecture studies. I was a lost youngster who didn’t know what he wanted and didn’t believe in himself. Back in the days it was believed that only the best and children of prominent people were being accepted in the school of architecture and I was neither. I was smart but lazy and I certainly wasn’t a child of someone important so I was convinced that I don’t stand a chance.

My parents talked me into meeting a famous architect, my aunt’s neighbor, so that he could check if I was a suitable candidate. It turned out he was sure that I was seriously training and drawing to get the spot, whereas my last drawing experience happened in kindergarten. He asked to see some of my works, which I didn’t have. All I took with me was a crumpled drawing pad and a pencil. I could tell he felt snubbed so he sat me down in front of a staircase at his office and told me to draw it. Back then I had no idea how perspective worked and how to do an architectural drawing, so I sat down and was given an hour to finish. He was feeling very disrespected and showed it in the way he was treating us. I remember my mom telling me that I no longer had to apply for the mentioned studies as long as I didn’t embarrass them at that time.

He took off for that hour and when he came back he said that I was a diamond in the rough. It was then when I started believing in myself and started attending drawing classes, a year before my exam. Things just took off from that moment.

Our magazine is directed to students and young architects so I’d like to ask about your college experience. You mentioned in one of the interviews that you tailored your programme to your needs and didn’t attend all classes although you passed all of them. Apparently, all you cared about during that time was designing. Do you think studies should be treated as a whole or there are some benefits to the selective approach that you had?

I didn’t have any grand plan back then and I am far from convincing anyone to follow my path – meaning focusing only on selected subjects and ignoring the rest. Unfortunately, this is what I did. Obviously, I’m smarter nowadays so I’d probably do it a bit differently and I would encourage everyone to focus on the most important things and swiftly pass the complementing subjects. Knowledge of various subjects is required to create and I admit that I’m sometimes missing this complementing context.

Let’s just start with the fact that it took me a bit more time to complete my studies as I was already devoted to designing back then. My university time stretched like spaghetti because I was working, actively participating in competitions and lived and breathed my projects. The remaining subjects were done in my last – fifth or tenth year of my studies, call it whatever you like (laugh). It was then when I got very motivated and started to attend all the lectures and even passed the exams very well. And I have to admit that the knowledge I gained during my last year is very useful to this day.

Bear in mind that what we learn during our studies is often a mystery to us. We start taking our baby steps in designing and we already approach constructions and installations, which truly become fascinating only later, when we know more and can shape the space in an interesting way and because we see the point in learning the technical side. These details become crucial as we see that no further step can be taken without them. And this is how, accidentally, I learned, because most of the technical subjects were completed by me towards the end.

But I’d also like to highlight that you don’t have to be the top of the class in every subject. There are things that are more important and you need to find some middle ground and not waste time on less important things. Design is the essence of our job and the other subjects are supposed to complement it. Even now, when someone comes to my studio with excellent grades across all subjects and all designs handed in on time, I cannot help but look at this person suspiciously. I want you to understand me well here, but I believe that a good architect is someone who devotes every moment to refine and enhance the project till the very last minute. Uses every possible chance to polish it even more. So to me, someone who has everything ready two days before the deadline seems a bit unreliable, is not fit for the job and cannot call himself a creator. I believe there are exceptions to this rule, such as Norman Foster, who is totally organized, but unfortunately I’m not that way and there are not a lot of people like him.

Again, I’m not trying to convince anyone to follow this path but there is a certain amount of wisdom in this approach. And, above all, design is the most important.

Given your experience – what the studies do not teach that is later crucial in the work of every architect?

Studies definitely don’t teach the practical aspects, that’s first. And second, if they were organized a bit better, they would have been a foretaste of the actual work. For instance, when you start in the studio and you participate in a project, you work with a constructor and other experts in their fields, encounter building regulations and area development plans. During the studies, our design is completely detached from our construction and installation classes. It would simply be enough to continue the task that we start in design classes in other subjects. Let’s say we’re designing a simple house, because you usually approach simple designs first. It would be great to design the installation and construction for this house in parallel. You don’t have to start with grand halls and count god knows what. It’s really worth learning on a smaller scale how all those aspects should interact with each other. If this worked like that we wouldn’t all graduate being such rookies. I really recommend to use your free time, if you have any, to supplement your school-based knowledge with on-the-job experience and participate in architecture competitions. This is essential if you want to become good at what you do.

Do you remember the first architecture competition?

The first one? Forgive my lapse of memory but probably it was a competition I took part in around the third or fourth year of my studies and I’m almost sure I didn’t manage to hand the work in on time. And this started a series of competitions.

Aside from the smart approach to design and the ability to lead the project from the beginning to the end in a cohesive and coherent manner, I learned to self-organize. You really need to learn how to manage yourself in order to lead the project – set up the task, come up with the solution, draw it out and submit. I really couldn’t handle all that at the beginning. I was a person that likes to polish things till the last minute and give everything enough thought. So I always had the issue with being on time and my first few competitions were a failure due to late submissions.

I need to go back in time a bit to explain this in detail. Before those competition s I won one competition and received an honorable mention in another. First, along with a few students I was invited to re-design a palace in Górzno, and it was the first competition that I won all by myself. For the second one, I joined forces with a few of my friends and we designed the expansion of Bauhaus in Weimar. It was also a time when I started getting to know my now-ex wife Marlena. And I remember that we were all supposed to take part in another competition and I really wanted Marlena to join our team, but a voting took place and she was banned from the group. So I figured out that I will ditch the group, as I believed her to be quite talented, and from now on we took part in competitions together.

The first competition that we attempted with one more person was a cultural center on some Japanese Island. We didn’t win but our idea was truly genius. It was supposed to be a place where all cultures and religions come together so our idea was related to the prism of white light and the rainbow that it forms. Each color reflected a different religion and contained a unit of truth and, when joined together, it represented the truth about God. The issue was that we couldn’t really translate it into the project. The idea was one thing but the design was a bit on the side of it. We could have executed it so much smarter. Obviously, we lost but back then we couldn’t understand why. Only with time we could figure out that we were too immature from the project point of view at the time – this failure came at the right time that allowed us to reach certain conclusions. Failures teach us much more than victories.

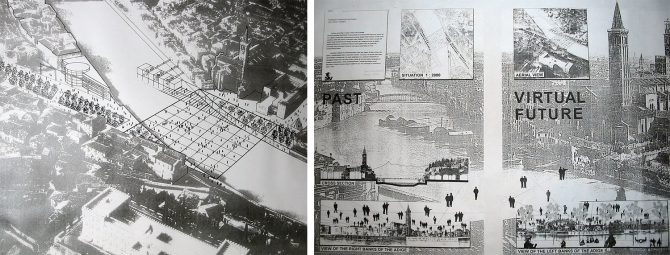

Then, as just the two of us, we participated in the competition for the bridge in Verona, which Marlena had spotted on the noticeboard in our faculty. Obviously, Verona is a beautiful city but the river is a bit detached from it due to a great flood that happened there in, I guess, the XIXth century. So they were looking for an idea to bring life back to the riverside. We were fiddling with the concept, looking for inspiration and two things came together here.

Firstly, I watched an episode of Sonda, a popular science programme, where they mentioned the concept of VR glasses. Now it’s nothing new but bear in mind it was 1994 and the concept of virtual reality was something groundbreaking. I was so amazed with the idea that I started to look for ways in which I could use it in the project. So, unlike everyone else, we stretched the bridge into a kind of glass piazza, so that it didn’t obscure the view as there were some cafes there. What we wanted was to create a virtual museum where people experience the past and can compare the reality to how it used to look in different times. The whole city planning reflected the times before the flood, where the river ran through the city. What was amazing, back then we had no computers, which is very shocking to modern students who keep asking me, how was it possible to design back then. Well, we did it all by hand. And I remember, which is maybe hard to explain without seeing this project that the look of this design seems a bit archaic, but the overall idea is really nice. There is a photo where you can see the past and the virtual reality, so suddenly people go through broken frames and symbolically enter the old world through architectural perspectives. What’s interesting, the project was almost finished and this motif with broken frames was added during the last night of drawing completely unconsciously. I was staying up late drawing and only in the morning I realized how freaking genius this idea is. Marlena thought that I came up with that but, and I am aware this will sound like I’m crazy, I felt like I was just a medium and I could understand what I drew only in the morning.

We sent everything a week after the deadline, as it was still the time where my planning was a bit off. I begged the lady at the post office to back-date the parcel so it seemed that we mailed it a week before. Something completely impossible to do today, but Poland was in a completely different era back then. I’m still thankful for that. However, for a very long time we didn’t know that we had been awarded with the third place because the letter with that announcement got lost. We only found out right before New Year, by accident.

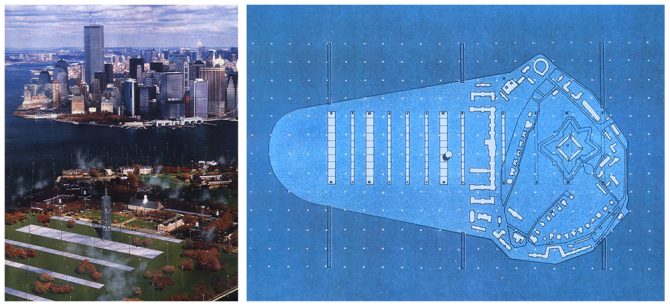

And that is where we did the second competition, the Governor’s Island. A fantastic space – a former military base between Manhattan and Brooklyn. Americans were looking for an idea for that place. The Cold War was over so stationing of troops was no longer needed there. What is interesting about this island, is that part of it is formed naturally and the other part is manmade from the ground dug out from the subway that was built between Manhattan and Brooklyn.

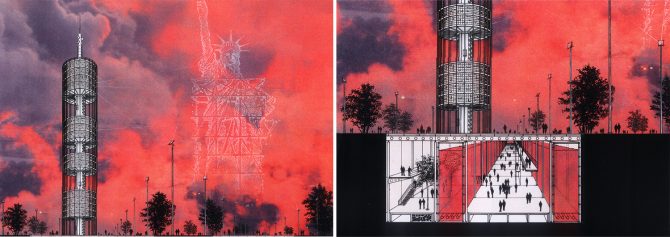

Americans are obsessed with monuments, mainly because they have so few of them, so this island is extremely protected, which was a crucial issue in this project. But we were still looking for an idea, and the bar code concept came to our mind. Each product is marked with barcode, storing the information about the product’s and the producer’s history, in a sense. So we marked this island with the barcode in order to attach the history to it. But how to read this barcode now? It’s not a shop where you scan that code. But this beam of light inspired us to rework the idea that Jean Michelle Jarre uses in his concerts where lasers cross, forming three-dimensional images. In order to achieve that you need artificial fog, so we covered the entire island with it – from Manhattan or Brooklyn it would have looked like a mysterious land. Additionally, we designed a forest of poles with movable mirrors and in the middle we placed a lighthouse emitting laser beams, so that it seemed that when you enter the island, you enter a virtual museum where you can see the building of the Statue of Liberty on a large scale. The poles did not impact the development of the island – they looked just like street lights because we put all of the infrastructure underground. We got an award for this project, but only when the attack on the World Trade Center happened, we truly realized how amazing and important this project was. If this project came to life, the two towers could still be present there as two luminous ghosts.

This project was done in 1996, and a few years later we saw an installation of New York based architects called Blur. We felt very sorry that they got to realize the project that we mothballed. But all we could do is to move on.

Those two projects are examples where the historical context plays an important role, but they also show how immateriality can complement architecture.

What did the competitions teach you?

First of all, each competition is a new project. And only the best and the most competitive people participate in them. Those who are average just complete their everyday projects and go on with their lives. But the architects who live and breathe this business, and who are later heard off, participate in the competitions so you’re racing with the best. If you lose, you have the chance to notice which project won and learn from just that. So if you make relatively more projects that you would have done just due to studies, it helps you grow.

Competitions bring new topics into the picture, each one tackles new issue and this is what our job is about. I am not one of those architects that would constantly want to design schools, hospitals or apartment buildings. I want to do everything and each theme is fascinating. There is always a first time for everything and those competition challenges teach you that. You get a task to design a theatre, so the first thing you do is to learn what theatre design is all about, research interesting existing designs here and there. Only once you acquire this knowledge you can move forward and suggest something new. This is the way both we and the architecture can grow.

It does also happen that those competitions shape our future. I’m thinking here about the Snøhetta case where ten young people did a competition on designing a big office and got to realize this idea. Sometimes your design remains on paper and sometimes you have the chance to bring it to life. So I really encourage everyone to do as many architecture competition projects as possible, doing them with due diligence and preparation, because it brings amazing growth. A few years into doing competitions my skills as a young architect were incomparably higher than people who would do four or five projects during a year or a semester.

Let’s face it, I didn’t study at Columbia University but in Gliwice. The faculty was cool but it’s a whole other level and I wasn’t exposed to the best architects and didn’t have classes with them. However, through the competitions I was in touch with their apprentices and judges who knew the top people in the industry. And it is like that until today.

Also, what I said at the beginning – the competitions teach self-discipline, organizational skills, resistance and obstinacy. They teach you the reality of this job, meaning that sometimes you need to stay up late at night, for multiple nights in a row in order to be on time. It’s a hard job, let’s be honest about it. One the one hand you need to be very sensitive, creative but you also need to be tough and possess mental strength. The competitions, if you manage to finish them, teach just that. These are the things that are not often being mentioned but an architect has to possess those qualities, so that he or she can motivate oneself and drive things till the end. Other than that you just learn and you temper yourself.

A few years ago you said “I want to race with the entire world even if the world is not aware of that”. To what extent did this sentence help you in your career and how did the competitions facilitate this?

We were always in awe of what is happening abroad – we never had the same opportunities, didn’t receive the same training and even later we couldn’t bring to life similar ideas. When I was starting school it was the last year of the People’s Republic of Poland. But the beauty of the creation process is that the beginnings are always the same – you sit down with a blank page and a pencil, just as the people we are in awe of. So the race takes place only in terms of ideas and this makes it the most beautiful and pure battle.

I always liked and had that competitive spirit as I believe I have an inner sportsperson. And this thought came to me towards the end of my education, when we started receiving all of the awards and I noticed that not only we are not inferior to others, we are often better. And I decided that I will not settle for comparing myself to only what is around me, because it was all mediocre. Just because we had some limits in Poland doesn’t excuse my actions as they are the only thing that counts. That’s why I came up with that motto. I thought to myself “Screw what’s around me, I’m lifting my bar as high as possible” and I wanted to race with the best. Sometimes lifting the bar this high doesn’t mean you will be able to make that jump. But at least you will jump as high as you physically can.

Those architecture competitions and meeting people from all around the world really gave me the sense that we are ok. After coming back from the States we decided to set up our own studio because we felt strong. Of course I had no idea back then what kind of responsibility this entails and what kind of problems this can cause, but I still had this young naivete. Now that I know all this I probably wouldn’t be as eager to repeat that, but back then, for the first time, we believed we could rock the world. Then came moments of doubts, and consecutive moments of strength and confidence. It’s a long and never ending process.

In one of your last interviews you mentioned that design really starts on paper. Why do you believe everyone should begin with a blank page and a pencil instead of browsing through Pinterest for inspiration and how does the beginning of the creative process look for you?

Well, coming back to this concept of racing with the entire world – if you want to do that, you have to do things that are your own fresh ideas that you can later develop and transform into a project. You cannot make copies. I am hypersensitive when it comes to that and it’s very easy to spot. When you hear people describing their projects you can often tell it’s all very shallow and no grand thought was behind it. You can clearly see the inspiration from something we already know.

In Poland we have many cases of such inspirations and it also irritated me a lot that even the school teaches you this spin-off approach to design. Seriously, our professors used to show us magazines and even convince us to copy in order to not reinvent the wheel. But it’s bad! We are also often shown photos of design showing just the outer layers of it, without trying to understand where it came from. There is no attempt to learn design from scratch. And I see a lot of potential wasted this way – young, talented people don’t understand certain processes so they don’t believe in themselves and this is how they later design, by mimicking others.

In my studio, through the years of laborious design, we learned discipline: there is a discussion, then drawing, ideas, concept and then we move forward in a logical way. And then a person joins the KWK team and I can already see them peeking, looking for existing examples and I always tell them to leave it alone as it is only an obstacle. The only thing you need to focus at the moment, is what we are doing. Don’t look too far and don’t look at the architecture, but look at the things that surround you. Think about what we have to do. This is the only way to achieve something new and fresh, and you will be followed and mimicked by a mass of students and architects. This is our goal – to create things that are coherent and logical and sometimes can turn out to be innovative. We are not pushing for things to be new but this approach to design allows you to find a completely fresh trace every now and again and this is fantastic.

The only way to achieve something new and fresh is to focus at the moment. This is how the best studios work – they do their own thing and don’t look around too much. If you follow their work you will see that they have revolutionary ideas but then they often develop them, they are polished and refined, almost like an evolution of the idea. And the architects that look to the left a bit and then look to the right have no identity and their designs have nothing in common. My professor, Andrzej Duda, once said that a good painter paints the same image for the entire life. I didn’t understand it back then and thought it must be completely boring (laugh). But if you don’t take it literally, it is exactly about the evolution of your ideas further and further and forming your own path.

It doesn’t mean, and I’d like to highlight that, that you need to completely detach yourself from what is happening in the world. You need to watch, follow and compare yourself to others, but not in the moment of coming up with ideas for design. And what I love most about architecture is that aside from creating a project, you create a certain solution that can be universal and that other people can derive and benefit from and interpret in their own way. A symbolic building block that appears in architecture, a new opportunity. This is why I’m so tough on people who try to copy – we need to draw and talk, draw and talk, and even if we look at other ideas and want to use one element, this needs to be discussed in detail and I can do it only with very aware architects.

What equals a good project for you?

It’s a hard question. We’re not talking about math that gives us a clear-cut answer, we’re talking about something unmeasurable. But, and this is very cool about conceptualism, when you get a good idea, you suddenly get an answer to a row of uncertainties, questions and problems. It’s truly amazing, but this is the way it works. Of course it is preceded by hard, wearisome work or followed by endless polishing of the initial idea, removing redundant elements, focusing on the most important things. I know it sounds a bit like magic, but somehow the idea comes to one person and not to the other. And, even if it sounds brutal, I need to mention that only 50 readers of this article will know what I mean and will be able to bring this to life, even if 100 thousand people read it, as they will do nothing about it. It’s quite brutal, but that’s how it works in the world of architecture. Because you need to be very talented, diligent, persistent and hard-working. I’m not trying to play the wise guy here, I’m saying this so people avoid disappointments. Some students think that all it takes to become great is to attend a lecture of a brilliant architect and finish a good school. It doesn’t. It is given to very few people. But it is true not only about our job – look at football players. I could have believed I can be the next Lewandowski but we both know how possible this is, because I simply lack his talent.(laugh)

But coming back to the good project – it obviously needs to be functional, related to the context even if it escapes the frames a bit, but it must be settled in. We need to understand where we are, what we are designing, what kind of local context is to be used, what the local craftsmen can do and what is the history of the place – this is smart design. Also, it should attract attention, trigger discussions and age well – it should stand the test of time. It’s the same with music – there are a lot of songs that seem great now but after 10-15 years only evergreens remain. It’s the same with our projects.

If you had to start all over again, what would you change?

I get this question quite a lot and my answers so far could be quite misleading so I will try to get it right this time. Of course, I would fix a lot of things on my path, I’d probably even graduate sooner and pay more attention to a few things, but I believe I mentioned that already. I certainly had a lot of luck and exhibited a great deal of persistence, and, except for the God given things, I tried really hard. But I’d like to target my advice to particular groups without assigning people to them.

To the small group of very talented students I’d like to say that just because you are talented doesn’t mean everything will sort itself out. Talent is not enough and you have to back it up with amazing, extra hard work. Take risks, sometimes you will need to put all eggs in one basket – without that, success is hard to achieve. It is worth to study and practice in good studios but focus on one or two so that you have enough time to learn. It will help to shape you and increase the chance of your success. But sometimes this still might not be enough, as our industry can be brutal at times. But I truly believe things are achievable if we really really want them.

A few words to those who are not extremely talented, but really want it – there might be situations on your path that might lead to great frustration and a perception that others have it easier. Please understand that not everyone can become the Lewandowski of architecture, our Foster, Koolhaas or Sejima. But you can still do great things with your team, in a great studio and feel fulfilled. The greatest people are talented in many spectrums but if you have special skill in one field, i.e.you have a great eye for detail, you can really be a great player in your team and contribute a lot. Not everyone needs to own their own studio.

But it’s never worth letting go, taking shortcuts and doing things we don’t feel, because they will come back to haunt us, sooner than later. I had many great colleagues that I competed with during studies who, due to many circumstances that I really don’t want to judge, did one or two bad projects that the clients kept coming back for and they became slaves of their own designs. I don’t wish this on anyone and this is why our choices are important especially at the beginning.

Robert Konieczny – Polish architect, member of the French Academy of Architecture since 2019. In 1999, he founded the KWK Promes studio, known for its conceptual approach to design that leads to frequent experiments and searches to improve the functionality of buildings and spaces.

Konieczny gained international recognition in 2007, when Dom Aatrialny by KWK Promes won an award in the World Architecture News competition for the best residential house in the world. Since then, he has regularly won awards in international architectural competitions, including the European Prize for Urban Public Space 2016 competition for The Przełomy Dialogue Center (Best Public Space in Europe) and the Wallpaper Design Award 2017 for the architect’s own house, Arka Konieczny (Best House in the World). KWK Promes projects have also been nominated for the Mies van der Rohe award.

At the moment, the activities of the studio are more and more focused on searching for solutions adapting architecture to the inevitable climate changes and the related challenges.

If you would like to ready more case studies like the one above please check our annual publication